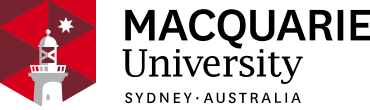

Cultural Burn, 2024. Painting by Leanne Tobin

On public space: an interview with Dharug scholar Dr Jo Rey

Dr. Jo Anne Rey is a Dharug community member, caring for Dharug Ngurra/Country (which covers most of the Sydney basin). She is currently working as an Associate Lecturer at Macquarie University’s Australian Harmony Centre for Ecosystem Futures located on Walumeda/Wallumatta. Her participation opens enormous research possibilities focused on the Durumbura (Lane Cove) River, with the inclusion of Dharug community participation, including through cultural fire and archeological sites present in the river valley, through biodiversity research including threatened native species, and with the ‘Koorabung’ enabling future on-water research and education that can benefit Dharug and other Aboriginal young ones and broader community. Jo’s academic journey has been deeply influenced by her family history.

What does public space mean to you?

Public space is Ngurra, that's our Dharug word for Country. Whether it's office blocks or public spaces, it's all Ngurra. Ngurra includes the stars, the waters, the marine life, the land life and everything inclusive within that space—that's Country. Everything is Ngurra and therefore public spaces are too and need to be cared for within our Custodial Tradition. Prior to 1788 everything was public space. It was very inclusive in comparison.

How does caring for Country relate to public space?

Traditionally everything was public space with clan area boundaries usually formed by the waterways. So, for example, where Macquarie University is, that's Wallumatta, and it's bounded by the Lane Cove River on one side and the Parramatta River on the other. We call the Lane Cove River the Durumbura Dhurabang. Dhurabang is our language word for river, and Durumbura is the area that is connected to Turramurra. The name Parramatta comes from the Burramattagal people. The Burramattagal people are kin to the eel, and the eel Dreaming story is connected to the river. The traditional custodial relationship with Ngurra is all around the recognition that we are kin to other living beings. Certain groups are kin to certain other species, for example, just as the Burramattagal people are kin to the Burra -the eel, the Wallumatta people are kin to the Wallumai, which is commonly described as the black snapper fish.

Custodial responsibility is absolutely critical and, for me, it's the inverse of the hierarchical notion, ever since the Enlightenment, that human beings are at the top of some kind of ladder and everything else is down below it. From our perspective, it's the absolute inverse. We are totally dependent upon the wellbeing of all these other beings. We only have to look at microbes in the soil to recognize that if the soil isn't healthy, the plants don't grow and if the plants don't grow, the animals don't have food. Of course, if we don't have animals and plants, human beings don't exist. The truth of the matter is, we are at the bottom of the ladder and the microbes in the soil are actually at the top, so it’s in our interest to care for all places, whether they're public or private.

Can you talk about caring for Country, even when Country is city. What sites and activations have you been involved with?

Caring for Country when Country is a city is quite difficult based on colonisation. The concept of private and public is foreign thinking in comparison to original and Aboriginal thinking. Our generation and the previous generations have had to fight to actually get heard or seen, but we're becoming a voice being heard through the education system. As of yesterday, I think we've got eight doctors that are Dharug now. And through that education system, we're trying to get it recognised that everyone is on Country, and in Country, and with Country, and as Country together. When you've got six million disconnected people and very few traditional custodians, then you must have allies in order to be able to achieve that custodial obligation of caring for Country.

I did my PhD on Dharug women's perspectives on Presences, Places and Practices. The women who were involved were connecting to places and saying how that place was important in their own personal lives and in terms of direct community. When I was invited to do a postdoc I thought, how do we get Dharug activation and presence back into this place called Dharug Ngurra (which is known as most of Sydney today) and has six million people, most of whom are disconnected from places from our perspective? The post-doctorate was called ‘Weaving Country across the City: Activating Dharug Ngurra’ and the website that is based on this project is called Dharug Country across the City (dharugcountryxcity.com.au). We centred on three significant places. Shaw’s Creek Aboriginal Place, Blacktown Native Institution site and Brown’s Waterhole.

One of the places we centred on is up in the Blue Mountains, where a lot of Dharug people are living these days, sometimes because they can't afford to live down in Sydney. There's a lot of activism going on up there and most of it is happening through a place called the Shaw’s Creek Aboriginal Place, which is at Yellomundee. Yellomundee is the name of one of the Dharug Karadji, who are our spirit people. For 15 to 20 years now there’s been a lot of activism such as gatherings, caring for Country, enacting ceremony, regeneration of language, and cultural fire, just to name a few.

My ancestors are connected to the second place, the Blacktown Native Institution (BNI) site. My Dharug ancestor partnered with a First Fleet Black African convict called John Randall and their granddaughter is my three times great-grandmother. Her name is Ann Randall. She was put into the Female Orphan School at Parramatta (1822 and from there she was transferred to the BNI in 1825. She was six when she first became institutionalised and nine when she was sent to the BNI. Her sister, Eliza, was too old to be institutionalized because she was 11, so it’s possible she would have been sent out to domestic labour.

So, the Blacktown Native Institution became very significant for me and based on that interest and connection, I participated in a group that managed to get that land and that site back into Dharug hands. I'd been on the working committee and then I was on the board of the the Dharug Strategic Management Group which had to be established in order for the return of the land to Dharug community. That was my giving back and my caring for Country in that place.

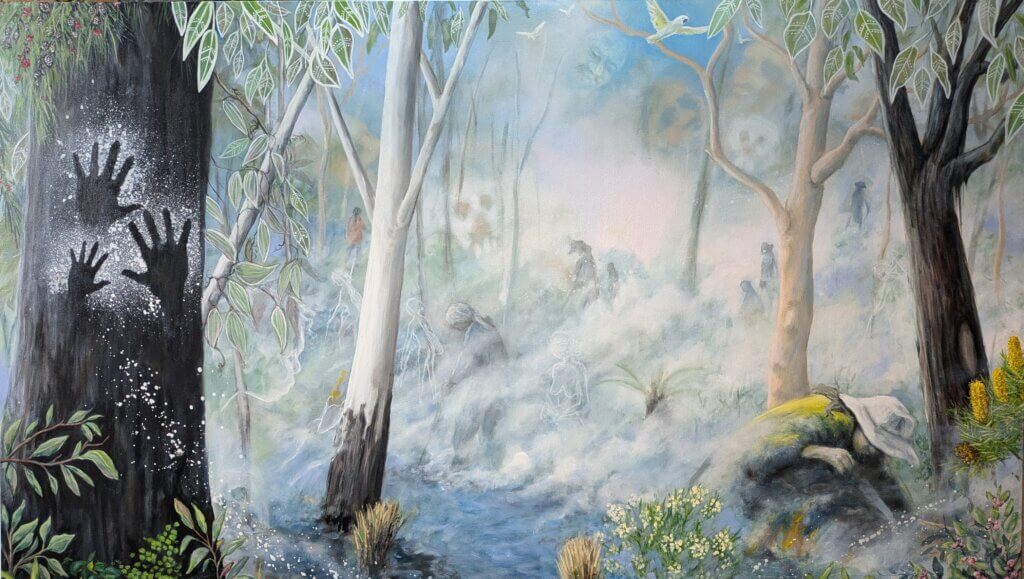

The third place, Brown’s Waterhole is down the hill from Macquarie University. It was only much later that I found out that the ‘Brown’ of Brown's Waterhole is also an ancestral family member, so this was a place of connection for me as well. I was made aware of Brown's Waterhole when I was asked to go down there one day with another Aboriginal woman who had a connection to the site. Several weeks later, Lauren, who was my research assistant at the time and was interested in doing her PhD on cultural fire came down to the waterhole with me. She was in what was then called the Department of Planning, Industry and Environment (DPIE) and part of the Cultural Fire Management team there. She spoke to them about Brown's Waterhole. Another of the team members was also doing their PhD, and they were doing it on women’s-led cultural burning. So, at that point, it became feasible that my project and the site of Brown’s Waterhole could contribute to their interest in cultural burning and have a Dharug women's-led burn there also. So, we got the funding and that's how it all happened.

A cultural burn is not just one day putting a lit match down. It took four years for it to come together – and through those years we experienced COVID and mega bushfires in south-eastern Australia, and floods impacting the river valley of the Durumbura Dhurabang. Everyone's consciousness was changing with all of these disasters and the fire people in particular were opening up to alternative ways of being with fire, rather than just seeing it as all about asset protection.

During the cultural burn journey we had stakeholder days, we had a women's camp, and that was historic because the Ryde Council allowed us to camp in a park that was proximate to the burn site. That was a first in the area—where Aboriginal people were allowed by local government to camp in a public space.

As part of that process of connecting to Country we got to know the site: we got to know the plants, the animals and the birds - there are enormous flocks of birds there. We also collected materials from the site to do artwork. We did dyeing using the materials from the site. We had smoking ceremonies and yarning around the campfire. So, all of that generates a reconnection to Country, and to each other, and to Dharug community and Dharug women.

The women’s camp was three days and the burn itself was another three days. We didn't camp at that time because of the physical fatigue of working. We did a prepping session for the site because it was so neglected. You had to actually get it into a safe space in order to do a cultural burn. We worked with l the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) requirements, with their assistance, through the burn plan, the review of environmental factors, and aspects that had to be done for safety reasons. They were really keen to support us, so it became a two-way educational relationality, with the Councils and the NPWS were involved. They saw and learned from us about an alternative way to have a relationship with fire in the public space, and about our caring for Country.

Through this work we moved into a recognition that dealing with all of this, place by place by place was not going to work. We had to have a consciousness of the whole river – or using today's language, the catchment of the river. We need to look at the problems that urban city life is creating for the river and for the creeks, which are having a negative effect on human beings, as well as the river itself.

The Dharug Durumbura Dhurabang (aka Lane Cove River) Wellbeing Project is an extension of what was the existing Macquarie University post-doctoral research involving activation and the regeneration of Dharug (traditional custodians’) cultural practices to Dharug Ngurra/Country-as-city at one river location: Brown’s Waterhole (BWH). The latest phase of this research involves Macquarie University, which has opened a centre called the Australian Harmony Centre for Ecosystem Futures. This phase is based on looking at sustainable futures through local places. A local ‘living laboratory’ kind of approach.

We're developing a stakeholder group now, and instead of three councils that were involved in the Brown’s Waterhole phase, we now have six councils, the NPWS, Macquarie University and Macquarie Business Park involvement. We're weaving a consciousness of the neighbourhood with the river at the centre. What's really important is this weaving country across the city project eventuated because all the women and the knowledges that were coming from Shaw’s Creek and Yarromundee came through, and the activation was there.

Could you talk a little bit about how you work with students and what impact learning through Country rather than about Country has on their understanding?

I hadn't quite completed my PhD when distinguished Professor Bronwyn Carlson invited me to develop a unit for first-year students which was really a basic introduction to Dharug Ngurra and Dharug people based on my thesis. The unit was called Dharug Country: Presences, Places and People. I developed that in 2018 and we started with 20 students. I think there's nearly 200 today. That unit was really centred on face-to-face engagement. That had to change eventually because so many students were doing things online, and due to COVID of course, but while I was teaching it, it was about taking the students out, getting them to connect with Country physically, so that they could actually move away from this place of modernity in the city, where you can hear the traffic all the time, you're in boxes of offices, you've got a time schedule as well as the fact that you might be coming from another country or your parents came from another country, and so the whole cultural dimension of connection to Country is not actually present.

What I was doing was getting the students to find a place that they connected to outdoors and to actually go there physically and listen, look, smell, perhaps taste if there's something there that can be tasted and just pause and focus and breathe. They then had to take a photo, record the sounds, bring it back to the class and tell them how that experience changed them. For some, it was just a tick a box exercise, but for others, it was quite rewarding for them to actually engage with Ngurra in that way. One woman, a musician in Tasmania, created a piano piece in response to that experience of going out on Ngurra. For me, that was fantastic. That's Ngurra connecting with her, allowing her to connect the way she could and be able to create something beautiful in response. That’s reciprocity. But you have to be there. You have to be present. You have to connect. You can't care if you don't connect. And without connection and caring, you can't belong. This is the philosophical underpinnings of what the postdoc was about, from my perspective, getting allies to actually understand our way of approaching the caring for Country topic in public spaces.

Public spaces are critical for creating connections for people to actually be able to connect and have a sense of belonging, because it's not good for your sense of wellbeing if you don't have a place of belonging and know where your place of belonging is. So from this mental health perspective public spaces are critical for human wellbeing. But it's not ‘let's just use the place’, that utilitarian approach, it is around giving back and that nature of reciprocity.

This journey has taught me the absolute significance of relationality. So, what is relationality? It starts with recognition - that you need to recognise that you want to have or need a relationship. Secondly, it involves partners having respect and the respect for both parties within that relationship. Then it involves equitable rights within that relationship, if that relationship is going to last. And then it involves responsibility if this relationship is going to last and be sustainable, we have to take responsibility for its maintenance. Then, like any relationship, you need reciprocity – it is not a one-way street. It's a giving and a taking together. And, finally, it's about restitution. Restoring the relationship is absolutely critical to having it as a sustainable approach. Now, this all makes sense when we're talking humans to human. When we're talking humans and other-than-humans is where our lore comes into play.

We need all those factors with other-than-humans going forward. Since colonisation that has never, ever, ever happened for Aboriginal people. There's never been any recognition of a need for respect for relationship. There's never been respect, there's never been equitable rights. There's never been responsibility for things that have gone wrong. There's never been reciprocity. There's never been restoration and restitution. So that's why we are in a position that we're in today. Colonisation has had such a negative impact because of the lack of relationality and the lack of those important facts.

Just as there's none of that being shown for First Nations peoples, it's never been really shown towards other-than-humans either, until now, when everything's under threat. There’s been a utilitarian approach of, how can we use the land? That's not a relationship mentality, it's a using mentality. And that's what has to change if we want to have sustainable futures. How we build and how we plan–all of these things are absolutely coming to the front of our minds now because of the climate change context.