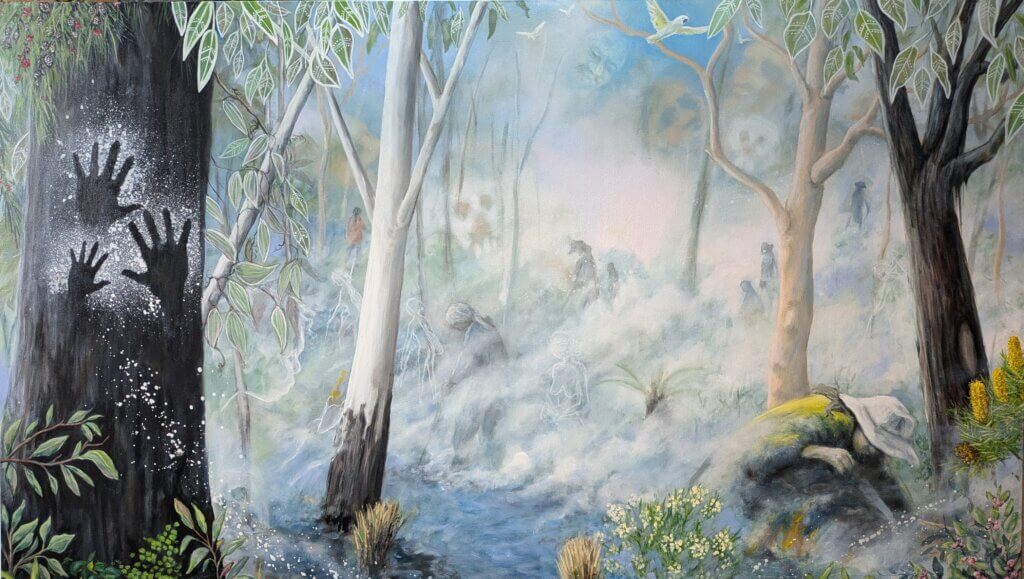

'Always was Always Will Be', Artist: Reko Rennie, Cracknell and Lonergan Architects for City of Sydney, Install 2012

On public space: an interview with architect and public art consultant Caroline Comino

Bringing delight to the public domain has kept Caroline Comino passionately engaged in the challenging and rewarding field of facilitating public art projects for the last 15 years. As a registered architect who has worked across the design and delivery of art and architecture to transform public space, Caroline has worked with mature artists as well as emerging, using her design background to closely work through design and technical issues and look at all opportunities that a site may present. Caroline has also had the privilege throughout her career to engage with First Nations People through the delivery of housing, public art and research, which has been key in shaping her deep respect for Country and Culture. Caroline has worked for architectural practices, universities, the Government Architects Office and commercial developers, so has a clear understanding of the purpose and value of art and culture and how it can contribute to the poetic dimension of a city.

Caroline started her own practice (CCA) in 2015 focused on the delivery of quality integrated public art. Her work has a strong focus on strategy, design and working closely with artists through to fabrication. This results in public art that is integrated, site-specific and unique as well as responsive to site and the community. Her work in public space has also led to her working on placemaking and art strategies. She sees the public art and the placemaking process as an opportunity to listen to community and Country and create unique artworks as well as build relationships and capabilities that can have a positive impact on the site and beyond.

Can you tell us a bit about how you came to focus on public space?

I studied architecture and worked as an architect for a while, but my interest was always in the crossover between architecture / art and public space, so that's sort of where it all started. I worked for over a decade on housing projects in remote and regional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and could see how important art and culture was to the health of each community. What's interesting about having the architecture background is that I always look at design in response to site, and that's how I approach public art.

I've worked in private architectural practices, for The Government Architect NSW and for developers for a number of years now, and I have worked with artists for many, many years. I've kind of done a full 360 in thinking about the commissioning, creation and activation of public space through art.

Private developers' understanding around the value of quality public space, especially Country-centred design, is increasing enormously. I see this as a big benefit to the work I do. It is of course sustained by the work of government in advocating for well-designed public spaces as well as the industry responding by doing better.

More and more I’m thinking about placemaking, culture and connections - it’s not always an art response that’s required. I’m very proud of the work I did with Stockland to find a beautiful studio space for Studio A artists and I think that’s an excellent way to support artists and add value to a development. I’m always looking for the win-win.

Can you speak a bit about the process of commissioning and realising public artworks. What are some of the most important considerations and biggest challenges?

It's a bespoke process for each project. It's important to respond to site and integrate with the landscape and architecture - rather than have art that is apart from it. A Designing with Country process is an excellent starting point if that’s part of the project design strategy. The way public art is procured can influence the success of the project. It is often procured as a separate contract from the rest of the building, and separate to the project designers, so it's in its own little bubble and I think that is why some public artworks look out of place or tacked on. I see that as a missed opportunity.

Ideally the client is really invested in having a good public art outcome, but art is often not considered on the critical path, so can become sidelined during construction. Just being aware that that's one of the main difficulties and knowing at what points you need to advocate for the artist is a big part of the job.

How these spaces are cared for is also a critical question. I'm trying to use more timber in public art projects but there is resistance, as it needs maintenance. Maintenance manuals often get put in a drawer never to be seen again. The question of who is going to organise and pay for ongoing activations is especially relevant, if you are creating multi-use spaces. Developers are understanding this more and more, and building on-site facilities teams.

What makes a great public artwork, and conversely what makes one fail?

You need to have good processes as well as engaged clients and stakeholders to make meaningful public artwork that is true to the artist's vision. I mean you can make a beautiful object without any of that but one of the biggest opportunities is in building relationships at every stage, even when procuring an artwork, there is an opportunity to connect with people in the community. You aren’t just delivering an object; you can achieve a lot more than that and still have a beautiful object at the end.

The public art that was delivered as part of the Metro upgrade has really raised the level of public art appreciation. It demonstrates a very integrated, very considered public art response and also reflects having a good budget and commissioning process. I think it's a bit of a turning point for public art in Sydney. You can't really get away with what people call 'plonk art' at all anymore.

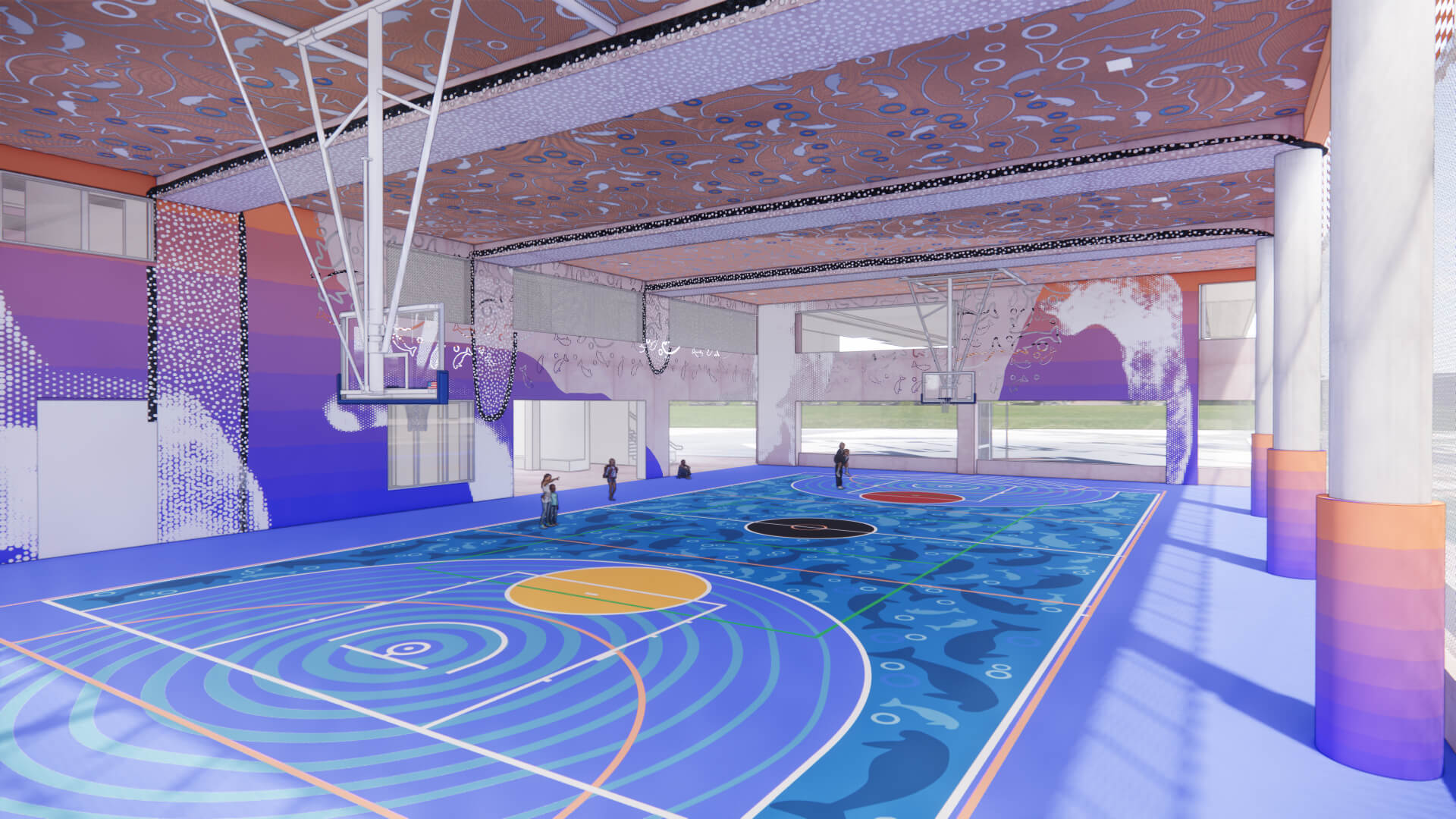

You worked on placemaking strategies for Stockland's MPark project at Macquarie Park. What were some of the challenges and opportunities around putting placemaking principles into practice there?

I think we were able to achieve so much at MPark because we were involved very early on in a long project, over many stages, and that has some real advantages. This means you can get involved early in writing your placemaking strategy and build relationships over time. For us it was about, first and foremost, who do we want to bring together on this project?

Public art is an excellent opportunity to bring community, Traditional Custodians, clients and local interest groups together to talk about Country. We were very fortunate that Stockland already had a good relationship with the local Dharug community, and we also knew that Macquarie University would be important to connect with. It's an ideal way to bring all those people together, to listen and actually physically create something and have it there for people to see and enjoy.

We had already worked with Macquarie University students through the PACE program for many years, so we could really understand what capabilities they could bring to the project. For one semester an interdisciplinary group of students focused on a particular site between Lane Cove National Park and a stretch of private land, so they could get different perspectives on the factors that were influencing that site. Their different approaches were really interesting.

We were very fortunate to work with Dr Jo Rey a Dharug community member and academic from Macquarie University, who generously shared her knowledge of this part of Country (Walumada) with the students and made all these connections possible. The Sociology students created QR codes to capture the views of residents and workers in Macquarie Park and the Environmental Science students looked at Shrimpton's Creek waterways marine life and pollution levels, this work is ongoing. Planning students mapped the different access points into the park and identified relevant strategies and plans. Together they helped us to think more broadly about the Macquarie Park precinct.

I think the amazing thing that's happened in the last few years is that the value of public land and public space has become one of the drivers in projects, whereas before I think people thought of it as the space that was left around the building. Macquarie Park, for instance, was a business park environment, with buildings in the landscape often fenced off and not much publicly accessible green space. The big difference for MPark is that it's been designed around a public green space. With the increasing densification of Sydney, public spaces now often act as people's backyard. That’s a big reason well-designed, usable and activated public space is so important.

That ties into public art. There are minimum requirements for public art, but I am finding that more developers are going over and above what the requirements are for public art. I'm doing a project now where there's no statutory requirement for public art, but the client is going to put a lot of money into it because they know that it will be to their commercial advantage if they do.

What are the best practice approaches to decolonising our public spaces?

I think having increased Aboriginal presence and visibility in public space contributes to the broader conversation and acts as a reminder of Indigenous sovereignty.

The first public artwork I worked on was with Reko Rennie in Taylor Square in 2012. It had the words 'Always was, always will be' wrapped around the building in neon. That phrase is commonly used in public discourse and conversations now, but it wasn't as widely used then. It wasn’t only this artwork, of course, but putting statements like this in the public sphere all adds to the public consciousness.

It's important to be led by people in the community that are connected to that Country - public space can become an opportunity to connect and understand Country. Creating spaces that are truly public and accessible, not commodified, is also a good start and a generous act which many developers are keen to do.

I presented an idea to a commercial client last week that was responding to the Frontier War history of that site and they were very keen to tell the truth of what happened there. I don't think I would have had that conversation even five years ago. The public’s understanding is becoming more sophisticated and there is a willingness and curiosity to genuinely engage with our difficult past.