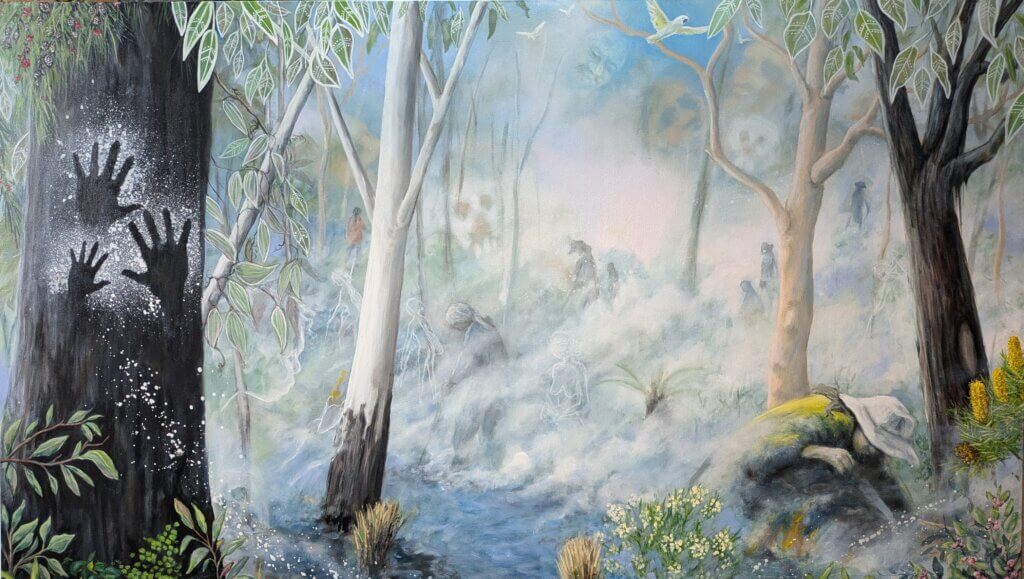

Parramatta Road, Petersham, Photo: Vanessa Berry/Mirror Sydney

On public space: an interview with writer and artist

Vanessa Berry

Dr Vanessa Berry is an award-winning writer and artist who works with autobiography, history, memory and archives. Her work centres around autobiography and its formal and experimental possibilities, arising from her background in zine making and DIY literary practices.

She is the author of Gentle and Fierce (Giramondo 2021), an essay collection about human and animal interrelationships, and Mirror Sydney: an atlas of reflections (Giramondo 2017), a collection of essays and hand-drawn maps that investigate the city’s marginal places and undercurrents, based on Vanessa's popular blog Mirror Sydney.

Could you tell us about a public space that means something to you. How would you describe this public space?

One of the most significant places in my writing and thinking about urban space is Parramatta Road. It's a thoroughfare that, more than any other roadway in Sydney, attracts a great amount of debate, and strong opinions about what it is and could be. Dominated by incessant traffic and lined by dilapidated buildings, the road is periodically brought into public attention with plans to 'fix' it. For example, a recent article in the Guardian, one of many such articles that have appeared in news media over the decades, was headlined 'Could Parramatta Road really become Sydney’s Champs-Élysées?'

So far, it is difficult to think of how it could be, realistically. It's undeniable that Parramatta Road both has, and is symptomatic of, serious and complex urban problems. As such it's revealing that it has remained in such a dire state for decades. As a writer and artist I'm interested in how observing, encountering and engaging with Parramatta Road through creative practices can add complexity to discussions around public spaces and their relationship to time. This involves how we understand them through their history, through encountering them in the present, and in imagining their futures.

Thinking about the role that this public space plays, what effect has this public space (or public space in general) had on your practice or sparked thinking or writing around the city?

Parramatta Road has been a foundational place for me in my writing and thinking about urban public space. Its resistance presents a challenge - how do you enter, engage with, and examine a space that's so resistant to these processes? To do so I use close observation, psychogeography, autobiography, and creative mapping as strategies. With Mirror Sydney, my blog, book and creative mapping project, I aim to draw attention to and celebrate places that are overlooked and hidden in plain sight, and encourage reflection on their presence and significance.

That Parramatta Road - like the suburb of St Peters, another area I have focussed on - is a resistant or difficult place provides a creative challenge. The subversive intent of psychogeography and countermapping provide good ways to engage with such places. Psychogeography, in its original conception by the Situationists in 1960s France, aimed to bring about revolution through attention to urban space and its atmospheres, particularly those which were difficult or resistant. Psychogeography has expanded from this original conception, but it retains a sensitivity to atmospheres and the importance of bringing attention to what is ordinarily not noticed.

Countermapping, which applies creative or subversive methods to spatial representations of place, is a practice that aligns well with psychogeography. In the case of Parramatta Road I mapped the road's landmarks, including the 24-hour Stanmore McDonalds, ghost signs for long-closed businesses, and notorious abandoned buildings such as the Midnight Star Theatre in Homebush. Any of these places would be familiar to people who had spent time in traffic - they are right there to be seen out the car window - but to present them as a sequence of significant landmarks encourages a different kind of scrutiny. The time and care that is instilled in hand drawing, for example, makes for a different kind of looking than the anxious view from the car.

Using autobiography and hand-drawing can be thought of as a creatively subversive act in a space that, in public discourse, is thought of mostly in negative terms. The connection of life stories and day-to-day encounters to a place like Parramatta Road opens up the potential to perceive and understand it differently. The problems of Parramatta Road are complex and cumulative, driven by social and political changes over the last century, but they essentially derive from the overwhelming amount of traffic which stifles life at street level. The swathes of demolition brought about by Westconnex only further alienate people from the streetscape. The creative scrutiny of Parramatta Road's details and atmospheres, and its presence in and through time, encourages a relationship of care and understanding for place that is vital for imagining its future. Important to the concept of life stories is to think of this in holistic terms - thinking about ecology, topography, and the shape of the land, which are all readily present if you experience Parramatta Road with these forces in mind. This approach is significant in understanding this as Aboriginal land with a history that long predates its recent identity as a road.

Parramatta Road remains a generative place for artists of all kinds, from writers such as Patrick White (for example, his short story 'Five Twenty'), to photographers such as Lyndal Irons, and artist/filmmakers such as Kate McGuinness (with the film 'I love long walks on Parramatta Road' ).

Some of the strongest impacts of these creative works comes from their observance and celebration of a place which is so often thought of as blighted and unworthy of anything but negative scrutiny. By embracing the idiosyncratic and the everyday, and the power of creative imagination, such works represent place and they encourage people to 'think like an artist' in troubled urban spaces, in order to perceive them, and their potential, differently.