Biodiversity in Place: putting the 'nature' back into nature strips

On 22 May 2024, to celebrate Biodiversity Day, the NSW Government Architect released a Biodiversity in Place Framework, providing a practical guide to bringing nature back into our cities, towns and suburbs. This initiative is the latest in a growing environmental revolution that has seen a flourishing of care and investment in Australia's public and private green spaces. Residents, communities and grassroots organisations have helped lead the way, particularly in those small yet significant public spaces - nature strips. Is the era of neatly mown suburban nature strips and lawns slowly coming to an end?

Nature strips are an interesting example of shifting attitudes towards the ecological and social transformation of our public spaces. While they are owned by local councils, maintenance of nature strips generally falls to the residents of the adjoining property. Many councils remind residents that it's a common, accepted practice throughout Australia that their keep their nature strips 'neat' and 'tidy' to create a 'good streetscape character'. What this means, in practice, depends on the interpretation of these words and on the attitudes of councils and communities.

How we plan and what we plant on our verges, backyards, balconies, public spaces, rooftops as well as in the land around critical infrastructure, such as our roads, railways and creek corridors, can make a big difference in the health of local environment.

From The Biodiversity in Place Framework1

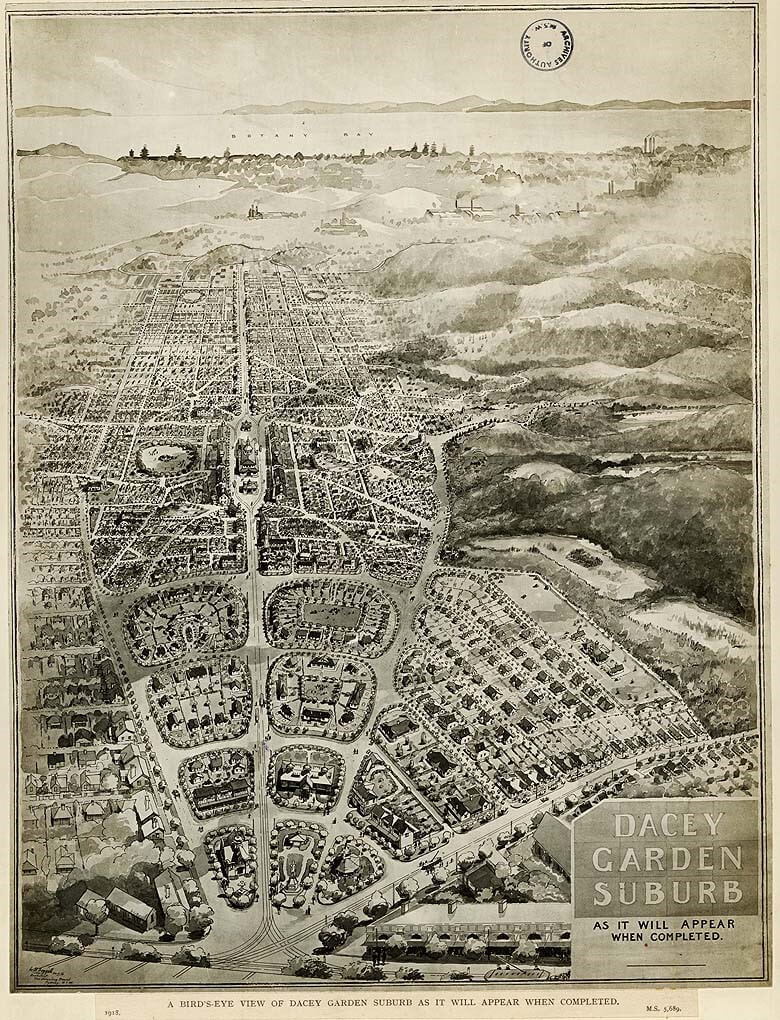

In his research on nature strips (or verges) Adrian Marshall says that "In Australia, the earliest of such planned nature strips can probably be found in Daceyville, Sydney, construction of which started in 1912 (Freestone, 2000). From then on, the nature strip became a ubiquitous element of the residential housing landscape."

Daceyville's design was inspired by Britain's Garden City Movement, which The Dictionary of Sydney describes as "an exercise in 'environmental determinism' that aimed at improving the morality, health and respectability of citizens by providing them with self-contained towns of ordered, visually pleasing streetscapes."

Marshall goes on to discuss individual and community attitudes around how these public spaces are understood, stating in 2019, "There are also deeper social forces behind the well-tended lawn (Ignatieva et al., 2015), for instance lawn can signify good morals (Hogan, 2003) and community mindedness (Carrico, Fraser and Bazuin, 2013). In contrast, verge gardening tends to be non-normative, in that it is often undertaken despite municipal authority restrictions, and it is – at least on the surface – against community expectations in so much as most verges are not gardened." 2

Since 2019 attitudes are slowly changing, and more and more councils are making it easier for residents to care for something other than lawn. Council websites generally outline what can and can't be planted and spruik benefits such as improved 'livability' or increased property value. It's still not a case of anything goes though, as councils are liable for the safety of these public spaces and nature strips can contain essential services such as sewerage, water pipes, telephone, power and gas. Generally, councils will not allow residents to plant street trees, but are increasingly open to more diverse ground cover and verge garden options.

Nature strips - a significant public space

"Our urban landscapes should not be considered complete on the day they are installed or mown, clipped, mulched, weeded and watered to maintain this stasis. Instead, our urban landscapes should be encouraged to grow and become resilient to change. They provide a home to our declining urban fauna."

NSW Government Architect, Biodiversity in Place Framework

When you consider the amount of space nature strips comprise, these small parcels of public land make up a large component of suburban environments and, in these climate- challenged times, increasing their biodiversity and resilience makes a lot of sense. Add to that the benefits of more community interaction, more interesting streetscapes and less lawn mowing, and it's no surprise councils across the country are starting to make it easier for people to invest in creating and caring for these spaces.

The language councils use to remind residents of their responsibility towards caring for nature strips can range from encouraging (e.g. City of Parramatta Council relies on "the goodwill and generosity of residents to mow the nature strip next to their property when undertaking the maintenance of their own property") to somewhat punitive, where residents may face fines for not regularly mowing their nature strip grass.

Nature strips are also some of the most contested public spaces too, raising issues around parking (you aren't allowed to park on nature strips in almost all council areas) through to different ideas about maintenance and access. In 2021/22 for instance, Wyndham City Council received 4083 complaints about overgrown grass on nature strips, compared to 931 complaints in 2015/16. [3]

In 2024 many local councils are reviewing their policies and guidelines for nature strips. In their recent Nature Strip Landscape Policy and Guidelines review, for instance, Maribyrong City Council asked residents to provide feedback on nature strip guidelines.

They received almost 250 responses, of which:

- the majority believed nature strips contribute to the look and feel of a street through colour/visual pleasure

- there was almost unanimous support for greater use of nature strips

- respondents would like to see more plants, more trees and more vegetable gardens.

Creating Biodiversity in Place

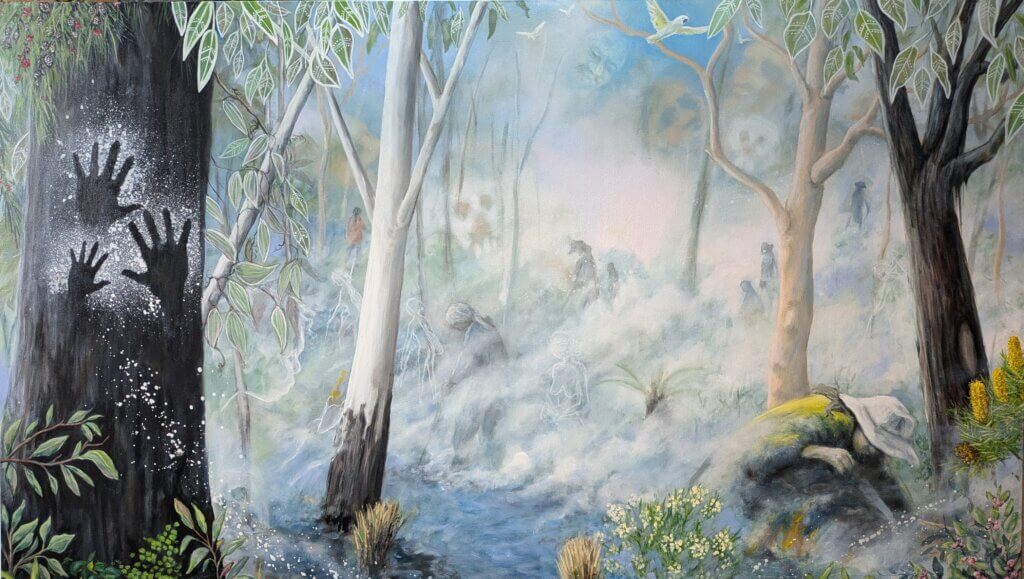

The Biodiversity in Place Framework acknowledges that "working with and supporting the nuanced knowledges and connections between First Nations and Country is essential for the success of future landscape health."

It outlines 6 key principles that go towards creating Biodiversity in Place:

- Nature as partner

- For humans and non-humans

- Guided by the landscape

- Highly diverse planting

- Sensitive and skilled management

- Connected across scales

The Framework also provides a list of online resources to support increasing biodiversity:

- Greener Neighbourhoods guide helps councils to create greener and shadier urban areas by developing or updating strategic urban forest plans. The guide is for all local councils across NSW who want to establish, build upon or re-envisage strategic planning for their urban forests. It gives guidance on how to understand, plan for, monitor and manage urban forests and promotes best practice and consistency in urban forest planning.

- Trees Near Me NSW is a state government initiative that maps trees and plants that are growing currently, as well as ecological communities that previously grew across NSW.

- The Atlas of Living Australia is an open access portal providing data on Australia’s biodiversity.

- iNaturalist.com is an online platform for the general public to contribute to citizen science and datasets of local biodiversity.

- BioNet and SEED are NSW Government GIS data sets that provide important mapping on ecologically significant communities.

- SIX Maps is an online mapping platform that provides cadastral and topographic information, satellite data and aerial photography for NSW.

- Which Plant Where is a plant selection tool underpinned by the latest scientific evidence, providing growers, nurseries, landscape architects and urban greening professionals with integrated tools and resources to develop resilient and sustainable urban green spaces for the future.

Biodiversity in Place explains "how communities, policymakers and industry can assist in reshaping nature-positive urban environments to reconnect people with larger natural systems. This will create cooler places, provide wildlife habitat and food, support biodiversity, improve mental health and beautify our living spaces. Supporting biodiversity represents a significant opportunity to connect with Country and foster collaboration and knowledge-sharing between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities to ensure sustainable and resilient outcomes."

Online groups such as Shady Lanes are also encouraging communities and residents to diversify their nature strip plantings. Their website provides links to a free Verge Garden Basics – Understanding the Space course on Substack and they also provide a list linking to local councils and their policies relating to natures strips or verge gardens.

While Australian suburbs may still be the land of the lawnmower, times are changing. Each small investment in creating and caring for our shared spaces, including our verge gardens and nature strips, contributes to nurturing our human and more-than-human environments in the present, and for the future.

[1] Biodiversity in Place Framework © State of New South Wales (Department of Planning, Housing and Infrastructure) 2024.

[2] Marshall, Adrian, Renaturing the nature strip: Spatial, environmental and social drivers of road verge extent, composition and resident gardening behaviour Adrian Marshall, PhD Thesis Melbourne University 2019. http://hdl.handle.net/11343/235809

[3] https://theloop.wyndham.vic.gov.au/local-law-review/nature-strip

Header image: Photo by Gilberto Olimpio on Unsplash